This Month's Big Lunar Eclipse

Newsletter January 2019

by Steven Forrest

If you live in North or South America, the sky will put on a very fine show on the night of January 20/21. Lunar eclipses are not rare, but ones that coincide with a so–called "Super Moon" are a lot more unusual. And that's exactly what you will be seeing, provided that no clouds get in the way: a particularly big Full Moon going dark, maybe even turning coppery–red in the process.

Caveat: absolutely guaranteed, the media is going to oversell it, leading to lots of disappointment among people who've been jaded by special effects in movies. I can see the hyperbolic Yahoo! headlines now: GIGANTIC MEGA-MOON ECLIPSES ENTIRE SKY! And of course somebody somewhere will have their fifteen minutes of fame by proclaiming some grand governmental conspiracy to conceal the fact that the Moon will collide with the Earth, probably due to some alleged malfeasance on the part of Hillary Clinton.

Ignore the hyperbole, but please, if you possibly can, have a look at this sky–show! Just keep your expectations somewhere south of seeing a real–life Star Wars up there that night.

Lunar Eclipses are languorous affairs, to be savored like long, slow winter sunsets or your last piece of chocolate. Totality, for example – the period of total lunar eclipse – lasts about an hour. Compare that with the frantic few minutes of a total solar eclipse. That's an entirely different beast, and admittedly a lot more spectacular. January's Moon–show, from the first, nearly–unnoticeable "penumbral" contact of the outer edges of Earth's shadow with the Moon to the final " not–with–a–bang–but–a–whimper" end of it all, runs about five hours.

The part you really don't want to miss is Totality. That begins at 11:41 PM–EST and ends at 12:43 AM–EST – and if you are in the Pacific Zone, lucky you: it's a far more convenient 8:41–9:43 PM on January 20. Starting maybe an hour earlier, it will be worth a peek – that's when the umbral period of the eclipse begins.

So make a thermos of hot tea and bring a blanket . . . unless you're in South America, of course. Then just kick back and enjoy.

The Moon Intensive

Taking care of the Moon in ourselves is the same as taking care of our hearts and souls. It is the secret of happiness. Unraveling its messages requires that we release ourselves from the strictures of reason and instead learn its mysterious, nonlinear, trans-logical language. “Being in touch with our feelings” is only one part of it. Creativity, dreams, healing and being healed—these are all lunar topics too, as are intuition, family, and “the Mother,” both literally and archetypally.

Taking care of the Moon in ourselves is the same as taking care of our hearts and souls. It is the secret of happiness. Unraveling its messages requires that we release ourselves from the strictures of reason and instead learn its mysterious, nonlinear, trans-logical language. “Being in touch with our feelings” is only one part of it. Creativity, dreams, healing and being healed—these are all lunar topics too, as are intuition, family, and “the Mother,” both literally and archetypally.In this workshop, we will deeply and technically consider the Moon and explore in depth the mostly forgotten mystery of the Moon’s eight phases.

Total lunar eclipses happen frequently, and unlike solar eclipses, you can see them from anywhere on our planet so long as the Moon is in the sky at the time. We'll have another one, for example, on May 26, 2021, then again on May 15, 2022 and yet another on November 8, 2022.

A dime a dozen, right?

What makes this particular lunar eclipse special is the fact that it coincides with a "Super Moon." The term is unfortunate because of the way it hypes the reality of the thing. But the Super Moon effect is real – and the idea behind it is simple. The Moon orbits Earth in an ellipse rather than in a circle. Sometimes it's closer to us – and thus looks bigger – and sometimes it's further away, and so it appears smaller. The variation in the Moon's apparent size is significant – a "perigee" Full Moon looks about 14% bigger than an "apogee" one.

For two reasons, people generally don't notice the difference: first, Full Moons only happen once a month, so it's a long time to wait between comparisons. Secondly, and more importantly, most Full Moons don't coincide with apogee or perigee, so their size is somewhere in between maximum diameter and minimum.

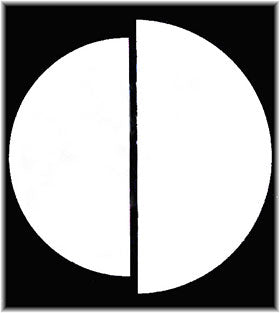

For those of you listening to this as a podcast, just trust me.

For those of you who are reading, have a look at this diagram on the right. It graphically represents the size–contrast between a perigee and an apogee Full Moon. You'll see that it's pretty dramatic, actually.

Here's the point of this astronomy lesson: on January 20, we get the double–whammy: a nice, big perigee Full Moon that just happens to go into total lunar eclipse. That combo–platter is obviously rare. I bet even aliens will be setting up their lawn chairs.

Switch your perspective for a moment: what if you were looking at this event from the surface of the Moon rather than from here on Earth? Well, lunar eclipses occur when Earth lies directly between the Sun and the Moon – so Earth's shadow is cast on the lunar surface. But if you were watching from the Moon, something more like a solar eclipse would occur, as Earth blocked out the face of the Sun.

It would actually be a magnificent thing to behold. You would see Earth as black disk with a brilliant flickering ring of orange, red, and crimson light surrounding it. If you think about what you would be contemplating, it'll give you goose–bumps. That flickering ring of orange, red, and crimson light is actually all of the sunsets and sunrises happening on the Earth at that particular moment, combined.

Pretty amazing, huh? But you'll need to catch the next bus to the Moon if you want to see it.

Our next step is closer to Earth, and it builds on what we just learned. What you are seeing projected onto the surface of the Moon during a lunar eclipse is actually the light of all those sunsets and sunrises. That's why a lunar eclipse is generally more "coppery" than black.

Of course we all know that sunsets and sunrises come in a variety of shades, ranging from Ho–Hum to Oh My God. This is why the color of each total lunar eclipse is so unpredictable. Can you predict whether tonight's sunset will be a memorable one? Probably not. Really, what you will be looking at on January 20 is Earth's weather, and even the weatherman gets that wrong a lot.

Less romantically, a lunar eclipse also reflects the level of pollution in our atmosphere. The volcano, Mount Pinatubo, blew its top in June 1991. A year and a half later, a lot of that dust was still in the air – and the next lunar eclipse was nearly black.

What will the eclipsed Moon look like on January 20? No one knows . . . not anymore than anyone can predict the weather that night.

Saros

Here we get a bit more technical. Read on anyway! For reasons that lie on the other side of a short science class, we just might possibly also be close to a real technical breakthrough in evolutionary astrology – one pioneered by an Australian fellow named Murray Beauchamp.

We will meet Murray in a moment.

There is a Sun–Moon opposition every month – that's just a simple Full Moon. Why then is there no lunar eclipse every month? Simple: Earth's shadow typically misses the Moon entirely. The Moon lies a bit above it or a bit below it. There may be a nearly–invisible penumbral eclipse, as the Moon passes through the faint edges of Earth's shadow. Another possibility is that the darker umbra of Earth's shadow might graze the Moon, creating a partial eclipse. Or it might be the Real Deal – a Total eclipse – like what's in store for us this month.

For a lunar eclipse to occur, the Moon must lie fairly close to the north node or south node. That assures that the Moon and the Sun are lined up not only in terms of their sign positions, but also in terms of their declinations. That's the critical ingredient. (The same is true for solar eclipses.)

Each eclipse, whether solar or lunar, has unique properties. How long does it last? Is it total or partial? How big does the face of the Sun or the Moon look? Is Moon lined up with the north node or the south node?

Well over two millennia ago, Chaldean astrologer–astronomers discovered that these identical eclipse–producing conditions repeat like clockwork. This enabled them to predict eclipses with great accuracy. They called this cycle the Saros. Its length is 18 years, 11 days, 8 hours. After that precise interval, Sun, Earth, and Moon return to approximately the same relative geometry. They are lined up the same way, and a nearly identical eclipse happens.

That last phrase – a nearly identical eclipse – is critical here. Earlier we saw that after this January's lunar eclipse, we will have another one in May 2021. That's only two years and four months later – way short of a Saros cycle. But it will be a different kind of event in terms of length, the visual size of the Moon, and so on.

So all of the eclipses linked to a specific Saros cycle are like a family–line, with strands of astronomical DNA held in common. Together, they are called a Saros Series.

There are separate solar and lunar Saros series, by the way. All of them are assigned numbers. Currently, for example, there are 41 active lunar Saros series happening. But each Saros series evolves, and eventually dies. Their life spans vary a lot, but you can think in terms of a Saros series lasting a very long time – say, a thousand years.

Are you getting dizzy yet?

Obviously this is complicated territory. Space and format mercifully prevent me from getting "book length–technical" in this newsletter. If you want to learn more, there is a fine article about the Saros cycle in Wikipedia – just Google "Saros (astronomy)" and it will take you directly to Virgo paradise.

You may be wondering what any of this has to do with astrology. Fair enough. "Not much," is a good initial answer. Your mileage may vary, but in my experience lunar eclipses, while visually captivating, have not impacted me much more than the monthly Full Moon – like you, I just grow a coat of fur, sharp fangs, and a compelling jones for human blood.

But, taken as a Saros series, these same lunar eclipses might provide a powerful missing link in the foundational logic of evolutionary astrology. The key is to remember that the nodes of the Moon are critical to eclipses – and that the nodes of the Moon are also the heart of what makes evolutionary astrology a unique discipline within the field. They are what links your chart to reincarnation – the long journey of your soul through human history. And just maybe lunar eclipses – and the Saros seris – can focus our attention on certain specific periods in history, perhaps periods which feel inexplicably familiar and real to you.

Earlier, I mentioned Murray Beauchamp. He has been part of my Australian apprenticeship program pretty much from the beginning, and he has developed some intriguing ideas about the lunar Saros series. His book, The Cryptic Cycle: Astrology and the Lunar Saros is unfortunately currently listed as "Out of Print – Limited Availability" on Amazon. You can still get it via the American Federation of Astrologers. You can also contact Murray directly at lunarsaros@gmail.com. He can mail you copies of his book for $20 Australian, plus postage.

Murray has lectured quite a lot in Australia and New Zealand, but his work is pretty much unknown in the northern hemisphere. His ideas are still formative, but I already find them extremely intriguing.

Here is his technique in a nutshell:

Look for the lunar eclipse immediately prior to your birth. It does not have to be Total; it can be umbral, or even penumbral. Find out which Lunar Saros series that pre–natal lunar eclipse belongs to. Then look for the first umbral eclipse in the series. That is the birth of the series. Murray says make sure it's the first umbral eclipse – not the first eclipse of the series, which is always penumbral and does not count.

By the way, The Cryptic Cycle contains tables and Internet links that will help you with all this.

Proof of the pudding? Well, it's early to use the word "proof," but here's what got me hooked:

The lunar eclipse that immediately preceded my own birth was part of Lunar Saros Series #116. That cycle began with an umbral lunar eclipse on June 16, 1155 A.D.

What follows is totally subjective and quite possibly meaningless. All I can say in defense of what I am about convey is that the inevitable first test of all astrological techniques lies in one's own personal experience. I would never teach anything that failed to illuminate my own life. We must of course eventually go beyond our narrow ego–world in order to make sure we are not turning a personal quirk into a cosmology. Before we open our mouths, we need to be sure that what we conjecture will be helpful to people in general.

But everything begins with your own personal astrological experience, and that's natural. No one should be ashamed of it.

The 12th century, when my own Saros series began, is the High Middle Ages. For what it is worth, I have always related in a strong, visceral way to that time. The Gothic cathedrals were rising. A kind of humanism entered Christianity, and with it, the onset of many of the very battles that I am still fighting in this lifetime, publicly and personally. When, many years ago, reading Rodney Collin's The Theory of Celestial Influence, I first heard of the Christian monastery at Cluny, I got chills. Was I once there as a literate monk? I thought so – and Cluny was in active upheaval around the time of the lunar eclipse that started "my" series. I did not know about my specific astrological connection to that time until I met Murray Beauchamp

In common with many Westerners, my knowledge of Chinese history is pitiful, although it has improved somewhat since I began teaching there a decade ago. There is a weird familiarity about China for me, which leaves me with no doubt that I've had lifetimes there. For some previously inexplicable reason, I lit up the first time I encountered the architecture, style and romantic history of the Song Dynasty – which I had never heard of before I began visiting that country. I felt sure that I'd had a lifetime in that period.

You guessed it: the fingerprints of Saros Series #116 are all over it. A quote from Wikipedia: "The Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279) refers to the period after the Song lost control of its northern half (of China) . . . During this time, the Song court retreated south of the Yangtze and established its capital at Lin'an (now Hangzhou)." That line gave me goosebumps too. I've spent many happy days in Hangzhou, and felt a compelling sense of deja vu there, especially in the Buddhist temples in the hills above the city.

My heart is telling me that Murray Beauchamp is onto something with his research into the lunar Saros series. Did I live in one or both of those times? If both, were my incarnations separated by some multiple of the Saros cycle?

If I had to formulate a hypothesis, it would be this: that a lifetime or lifetimes spent around the beginning of the lunar Saros cycle reflected in the lunar eclipse just before your birth represent the roots of the karmic issues with which you are reckoning today.

I would also like to pursue the obvious conjecture that we might tend to take birth around other subsequent lunar eclipses in "our" Saros series. I've not yet explored that possibility.

Will time prove this hypothesis to be helpful or not?

Like almost everything of lasting value in astrology, the answer will not come from one person, but rather from marrying the idea and the entire astrological community in the alchemical cauldron of time. We may know the answer in a generation or two, in other words – but only if we ask the question.

In any case, it is something to ponder as the big–as–it–can–get Super Moon turns to copper on the night of January 20.

One last thought – the Lunar Saros series of which this upcoming eclipse is a member began on July 7, 1694. As time goes by, it will be interesting see if events around that historical period have any apparent karmic relevance to some of our friends who are in utero at the moment. I also note that The Bank of England was founded in that year and it is the model on which most modern central banks are based. I find this intriguing, especially in light of Uranus crossing back into Taurus on March 6 and the world's economy seeming to be on the verge of major evolution or even revolution as we face what people are increasingly calling "late stage Capitalism." Is something about our relationship with money that began in 1694 with the founding of the Bank of England coming to a time of karmic reckoning? We'll see . . .

-Steven Forrest